Paul’s letter to Philemon presents us with a challenge. Imagine taking this letter to various movie studios in the hopes it gets turned into a film. The problem that studio executives will have is there is no clear villain.

Sure, Philemon is fraught with problems— he is a slaveowner, after all—but Onesimus doesn’t have clean hands, either. Read just about any scholar, and they will tell you that when Onesimus decides to leave, he faces a dilemma any slave faces: How will he fund his flight? How will he eat? What will he do about travel and lodging expenses?

It’s a cold world out there, and Onesimus is ill suited to thrive in Roman society as a free person. So Onesimus does what most slaves would do—he steals from Philemon. Paul alludes to this when he says, “If he has wronged you at all, or owes you anything, charge that to my account” (Philemon 18). In the drama of their relationship, there is mutual culpability. Please don’t hear this as “equal culpability,” as if owning a person is on par with stealing possessions. Rather, “mutual culpability” is an admission that both have stolen from each other. Philemon has stolen Onesimus’s freedom, and Onesimus has stolen Philemon’s possessions.

This is what sin does and why friendship is so hard. Sin makes thieves of us all because the epicenter of sin is self. All of us are obsessed with our own gratification, and we will not stop until we are satisfied.

Some men never make it to the marriage altar to know the joys of friendship with a wife because they are obsessed with taking from a woman’s body to satisfy themselves. Others will never know the kind of friendship that covers the arc of “I will” to “I did” because they put others down to elevate themselves through gossip or slander. Some are like one man I know who always cozies up to the “cool kids.” The moment he finds someone “cooler,” he leaves to join the new group. This is a form of stealing by which people take from others’ success to build their own image.

And then there is the opposite dilemma, where people surround themselves with friends who share their same station in life, whether they have been hurt like them or are experiencing the same economic struggle. We understand friendship often begins on a note of affinity. The problem, however, is that when one friend begins to do better and emerges into a new stratum of well-being or success, the other person crucifies the friendship, no longer able to steal from their failure to feel good about themselves.

You may wonder if there is any hope for Philemon and Onesimus to be friends. How in the world will the two thieves sit at the table of friendship? This then leads us to ask questions of our own relationships. Is there any hope in a world marred by sin, which tears at the fabric of human relations, for deep, abiding friendship?

Simply put, the letter to Philemon unlocks the door and shows the way to enduring friendship. If we heed Paul’s instructions, we will know the joys of sustained friendship and experience a kind of meaning that no paycheck or position can ever satisfy.

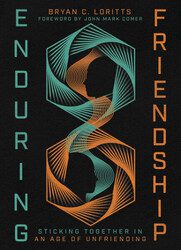

Adapted from Enduring Friendship by Bryan Loritts. ©2024 by Bryan Loritts. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press. www.ivpress.com.

Bryan C. Loritts (DMin, Liberty University) is teaching pastor of the Summit Church in Durham, North Carolina. He has dedicated his life and ministry to seeing the multiethnic church become the new normal in our society. He is also vice president for regions for the Send Network, the church planting arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, where he is responsible for training church planters in multiethnic church planting. He has been a featured speaker at the Global Leadership Summit and Catalyst. His books include Insider Outsider, The Dad Difference, The Offensive Church, and Enduring Friendship. Follow Bryan on Twitter: @DrLoritts Follow him on Instagram: @Loritts Find him on Facebook: Bryan Loritts Visit his website at BryanLoritts.com

Bryan C. Loritts (DMin, Liberty University) is teaching pastor of the Summit Church in Durham, North Carolina. He has dedicated his life and ministry to seeing the multiethnic church become the new normal in our society. He is also vice president for regions for the Send Network, the church planting arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, where he is responsible for training church planters in multiethnic church planting. He has been a featured speaker at the Global Leadership Summit and Catalyst. His books include Insider Outsider, The Dad Difference, The Offensive Church, and Enduring Friendship. Follow Bryan on Twitter: @DrLoritts Follow him on Instagram: @Loritts Find him on Facebook: Bryan Loritts Visit his website at BryanLoritts.com